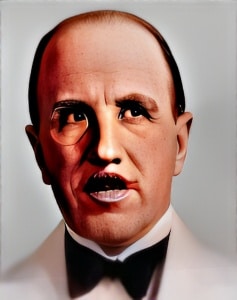

John Bunny (September 21, 1863 – April 26, 1915) was an American actor whose career spanned the transition from stage to film, leaving an indelible mark on the early days of cinema.

John Bunny (September 21, 1863 – April 26, 1915) was an American actor whose career spanned the transition from stage to film, leaving an indelible mark on the early days of cinema.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Bunny’s journey into entertainment began as a stage actor before he seamlessly transitioned to the emerging world of film. His contribution to the film industry, particularly during his time with Vitagraph Studios, established him as one of the most recognizable and beloved actors of his era.

Bunny’s early life was marked by a diverse heritage, with an English father and an Irish mother. Born on September 21, 1863, in Brooklyn, New York, he received his education in the city’s public schools. His initial foray into the working world involved employment as a clerk in a general store. However, the lure of the stage proved irresistible, leading him to join a small minstrel show at the age of twenty.

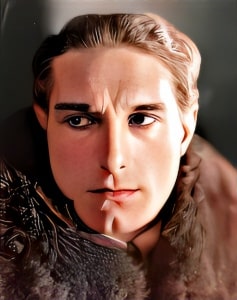

Over the next twenty-five years, Bunny carved out a successful stage career, working with various touring and stock theater companies. His theatrical journey took him to cities such as Portland, Seattle, and locations along the East Coast. Eventually, Bunny found his way to Broadway, where his performances in productions like “Aunt Hannah” (1900), “Easy Dawson” (1905), and the Astor Theatre’s inaugural production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1906) garnered acclaim. One of Bunny’s notable roles during this period was his portrayal of the Jailer in the 1911 cinematic adaptation of Charles Dickens’ “ A Tale of Two Cities.”

In 1915, Bunny sat down for an interview, reflecting on his decision to enter the film industry. He identified the burgeoning popularity of movies as a significant factor influencing the decline of the stage. Despite facing initial reluctance from Vitagraph Studios due to salary constraints, Bunny insisted on joining and began his film career around 1910.

Vitagraph Studios became the platform for Bunny’s cinematic legacy, where he starred in over 150 films. Notably, he frequently collaborated with comedian Flora Finch, creating a series of popular comedies known as “Bunnygraphs” or “Bunnyfinches.” These films often featured situational humor in domestic settings, a departure from the rowdy slapstick prevalent in that era.

One of the exemplary films in the Bunnygraph genre was “A Cure for Pokeritis” (1912), where Bunny’s character’s wife orchestrates a fake police raid to curb her husband’s gambling habits. Bunny’s films gained popularity for their humor grounded in comedy of manners rather than slapstick, offering a more polite and respectable form of situational comedy.

Despite his relatively short film career, Bunny’s impact was substantial. He was one of the earliest actors to master the art of conveying emotions without the use of words. Critics praised his extensive and flexible facial expressions, noting that he made a significant contribution to the emerging art of acting in silent films.

Bunny’s influence extended beyond the screen, with contemporaries recognizing his role in presenting refined comedy in the realm of photoplay. His films helped elevate the medium’s status, proving that a real actor could achieve success without resorting to vulgarity or horseplay.

The Washington Times in 1916 credited Bunny with rescuing screen humor from crude forms and placing it in the hall of fame. The actor’s focus on comedy of manners, a polite and respectable form of humor, distinguished him from the prevailing lowbrow, crass, and often violent humor of the time.

Despite his on-screen amiability, Bunny’s relationships behind the scenes were not universally positive. Reports suggest that he had a strained relationship with his frequent co-star, Flora Finch, and some colleagues found him arrogant and challenging to work with. Despite such interpersonal challenges, Bunny’s contributions to early cinema were undeniable.

Tragically, Bunny’s career was cut short when he succumbed to Bright’s disease at his home in Brooklyn on April 26, 1915, just five years into his film acting career. He left behind a wife and two sons and was interred at the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn. His death marked the end of an era, but his legacy endured.

The New York Times editorial following Bunny’s death emphasized his status as the living symbol of wholesome merriment, resonating with audiences across the country. Bunny’s fame reached global proportions, with his name becoming a household word wherever movies were exhibited.

Despite Bunny’s genial on-screen persona, some of his contemporaries held less favorable opinions. Vitagraph co-founder Albert E. Smith revealed that Bunny and Flora Finch “cordially hated each other,” shedding light on the less harmonious aspects of his relationships within the industry.

After Bunny’s passing, Samuel Goldwyn attempted to continue the Bunny legacy by signing George Bunny, John’s brother, for films in 1918. However, the attempt was not successful, and new comedians emerged, pushing Bunny’s memory into obscurity. Nevertheless, Bunny received posthumous recognition when he was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960, highlighting his lasting impact on the film industry.

One of Bunny’s films, “Pigs Is Pigs” (1914), was preserved by the Academy Film Archive in 2010, allowing modern audiences to glimpse his contributions to early cinematic comedy. Despite evolving comedic tastes, Bunny’s films remain a testament to his unique style and the pivotal role he played in shaping the landscape of silent film comedy.

Loading live eBay listings...