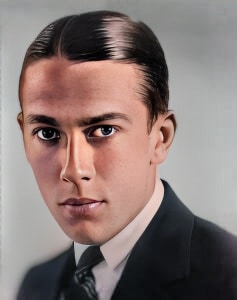

Wesley Ruggles, born on June 11, 1889, in the cinematic hub of Los Angeles, California, carved his niche in the film industry as a versatile talent.

Wesley Ruggles, born on June 11, 1889, in the cinematic hub of Los Angeles, California, carved his niche in the film industry as a versatile talent.

While younger brother Charlie Ruggles pursued acting, Wesley’s journey encompassed acting, directing, and a distinctive foray into the realm of Technicolor musicals. From his early days as a silent film actor to his acclaimed directorial efforts and an unexpected detour into a cinematic misstep, Ruggles left an indelible mark on the evolving landscape of American cinema.

Ruggles embarked on his cinematic odyssey in 1915 as an actor, sharing the silent screen with luminaries like Charlie Chaplin. Notable among his early roles was portraying a shipowner in “ Shanghaied,” showcasing his versatility in both dramatic and comedic performances. However, it wasn’t long before Ruggles turned his gaze toward the director’s chair, where he would ultimately make a lasting impact.

Transitioning to directing in 1917, Ruggles would go on to helm more than 50 films, showcasing a diverse range of genres and styles. One of his notable ventures into literary adaptation was the silent version of Edith Wharton’s novel “The Age of Innocence” in 1924. This early exploration hinted at Ruggles’ ability to navigate the complexities of storytelling across different mediums.

Ruggles’ breakthrough came in 1931 with “Cimarron,” an adaptation of Edna Ferber’s novel that depicted the challenges faced by homesteaders in the Oklahoma prairies. This Western not only marked a pivotal moment in Ruggles’ career but also made history as the first of its genre to win the coveted Oscar for Best Picture. The success of “Cimarron” catapulted Ruggles into the limelight, setting the stage for a string of directorial triumphs.

In the following years, Ruggles showcased his directorial prowess in a variety of genres, displaying a keen ability to navigate both drama and comedy. “No Man of Her Own” (1932), a light comedy starring Clark Gable and Carole Lombard, demonstrated Ruggles’ versatility in eliciting laughter while maintaining a touch of romance. The comedic allure continued with “I’m No Angel” (1933), featuring Mae West and Cary Grant, revealing Ruggles’ skill in handling charismatic and dynamic personalities.

“College Humor” (1933), a musical comedy with Bing Crosby, added another dimension to Ruggles’ repertoire. His ability to navigate the nuances of musical storytelling foreshadowed an unexpected turn in his career—a Technicolor musical that would prove to be both a critical and commercial challenge.

The year 1946 saw Ruggles collaborating with the Rank Organisation for “London Town,” a Technicolor musical featuring Sid Field and Petula Clark. While Ruggles had not previously ventured into the musical genre, his American background seemingly positioned him as the ideal choice for this cinematic experiment. The film, however, proved to be one of British cinema’s most significant failures, earning the unfortunate distinction of a critical and commercial flop. This ironic twist marked the culmination of Ruggles’ directorial career, leaving behind a cinematic curiosity.

Wesley Ruggles bid farewell to the world of filmmaking on January 8, 1972, in Santa Monica, California. His final resting place, alongside his brother Charles Ruggles, is in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale, California. As a tribute to his enduring contributions to the motion picture industry, Ruggles earned a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6400 Hollywood Boulevard.

In retrospect, Wesley Ruggles’ cinematic journey is a tapestry woven with diverse threads—starting as an actor in the silent film era, achieving acclaim as a director with an Oscar-winning Western, and concluding with an unexpected foray into Technicolor musicals. While the cinematic landscape evolved, Ruggles’ legacy endures as a testament to his adaptability, creativity, and the unpredictable nature of a directorial career that navigated both triumphs and challenges.

Loading live eBay listings...